The Science of Canning Isn't Settled And Why That's a Good Thing

You May Want to Rethink Using Grandma’s Old Recipes—As Hard as That Is to Hear

I grew up canning with my country grandma Clara—a practice so profound, I created Clara’s Canning in her honor, and it has taken me many places. I’m deeply passionate about sharing the joy of canning with all who are curious, from beginners to seasoned vets. It’s a tradition worth preserving with every fiber of our being. Canning means we can eat locally year-round. Our gardens don’t have to stop feeding us when the first frost comes. We can share our bounty with one another in a beautiful package, and it can provide food security for years to come.

Grandma Clara, seated beside Grandpa Winston, cradling baby Amie. She was the canning queen—feeding her ten children and countless grand kids with skill and heart.

“But my family has always done it this way, so it’s fine.”

I hear this all the time. And as a certified Master Food Preserver, I want to explain why it’s time to update our thinking—while still honoring what came before.

When done correctly, home canning is incredibly safe. But when it’s done improperly, it can, in fact, be deadly. The thing is—doing it properly is amazingly easy. All you have to do is follow a tested, approved recipe and method—ideally from publications within the last 5 to 10 years. If a recipe is older than that, it’s a good idea to double-check the source online to see if any updates or safety revisions have been made.

So I’m not sure why so many people are dead set on repeating the wrong part of history here. Maybe some of that stems from not knowing the history of canning.

Given that, let’s take a step back and look at where this all began—and why it matters more than ever today.

Nicolas Appert, the godfather of home canning. A surprisingly severe-looking man for having invented such a whimsical practice. Source

The first inklings of canning as we know it currently came from a French confectioner named Nicolas Appert. In 1795, Napoleon called on his countrymen for ways to feed troops on the road, offering a grand prize of 12,000 Francs. Appert answered the call. Reasoning, “If it works for wine, why not food?” he began experimenting with sealing food in bottles and applying heat. By 1808, Appert had developed a never-before-seen method of “bottling” food to make it shelf-stable, and was awarded Napoleon’s reward. He penned the first book on the subject in 1811, The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal & Vegetable Substances for Several Years, and the art of canning was born.

At the time, Appert didn’t understand why this process worked—he believed it was air that caused food to spoil, so he sought to keep it out. It wasn’t until decades later that Louis Pasteur would prove that microorganisms were the true culprits behind spoilage. The combination of Appert’s ingenious method and Pasteur’s evolving understanding of microbiology formed a divine union that would continue to develop over time.

The Unification of Canning and Modern Science

Some may scoff at that. I’ve heard everything from “Whatever the government says, do the opposite!” to “The USDA just wants to keep us from being self-sufficient!”—even comparisons to terrorism and conspiracy. I’ve seen and heard a wide range of rationalizations for using either very old or entirely made-up recipes.

Some might assume this makes me a “trust the science (without question)” type. But that is simply not the case. I’d even hand it to the USDA cynic, in one way: I do not stand unequivocally behind everything the USDA says or does.

Because “the science” is not—nor has it ever been—settled. Science, in its purest form, is a constant journey of trial, error, documentation, discovery, and the evolution of understanding for the greater good. The progression of home canning from its origins to today is a perfect example of this pursuit.

No single person pioneered home canning. No one body regulated it in its entirety. Its history is a monumental feat of human collaboration and resilience—an ongoing testament to our ability to learn, adapt, and preserve. This isn't about "crooked science" or government control. When we adopt an all-or-nothing mentality, we all lose. Not every part of modern science or regulatory policy is flawless—but not everything is a conspiracy either.

Since Appert’s debut, we've seen milestones like:

1812: Peter Durand’s invention of the first tin can, revolutionizing commercial canning.

1858: John Mason introduced the threaded glass jar with a rubber lid seal—designs we still use today.

1872: Amanda Theodosa Jones pioneered the “Jones Method,” improving canned food quality.

1915: Alexander Kerr released the iconic two-piece lid that "pings" when sealed.

1917: The USDA declared pressure canning the only safe method for low-acid foods.

1940s: Home canning surged during WWII as part of the victory garden movement.

Each of these turning points brought trials and revelations. Through them, food preservation became the deeply refined science it is today. But it wasn’t without sacrifice— and while exact numbers are hard to pinpoint from the 1800s-1900s, many lives were lost to food borne illnesses like botulism, which once carried a near 60% mortality rate. I believe it dishonors the lineage of canning to dismiss these casualties.

Examples of Home Canning Resulting in Botulism Outbreak & Death in Recent History:

1924 – Albany, Oregon: Twelve individuals died after consuming home-canned green beans at a family gathering.

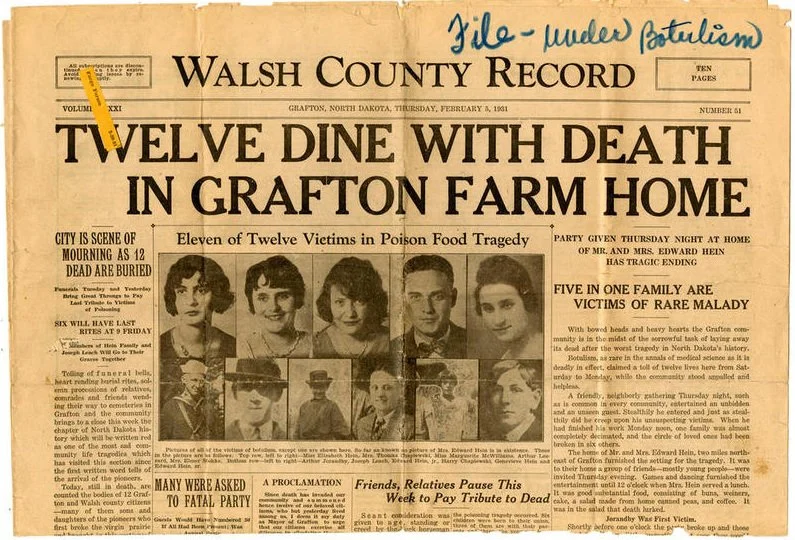

1931 – Grafton, North Dakota: A family party turned tragic when home-canned peas served in a salad led to 12 deaths, including members of the host family and guests.

1977 – Pontiac, Michigan: An outbreak of botulism occurred at a restaurant where home-canned peppers were used, resulting in 59 people falling ill.

1996 – Teton County, Idaho: Three family members contracted botulism after consuming improperly home-canned carrots during a Christmas Eve dinner.

1999 – Toronto, Canada: Six individuals, including a parish priest, were affected by botulism after consuming improperly home-canned tomatoes.

These are some of the most significant examples of foodborne illness and death related to home-canned goods, but certainly not the only in recent history.

The original newspaper cover reporting the Grafton Farm home botulism tragedy, source.

Although we’ve just focused on outbreaks & deaths related to clostridium botulinum from home canning, it’s important to note that botulism is, in the grand scheme, relatively rare. So why is it emphasized so heavily in canning communities? For one, it represents a worst-case scenario—an illness that can be fatal and must be taken seriously. Additionally, when we follow all the recommended precautions to prevent c. bot, we are also protecting against a wide range of other microbial and fungal contaminants that could compromise the integrity of home-canned foods.

Since the 1950s, we've seen a significant decline in illnesses and casualty related to home canning. This shift is largely due to increased education, rigorous lab testing, and widespread public awareness—much of this awareness being led by Master Food Preservers and university extension programs. Today, many people haven’t heard the cautionary tales that once circulated widely, nor do they personally know anyone who’s been harmed by improperly canned food. As a result, we’re at risk of slipping into that familiar pattern of “out of sight, out of mind” when it comes to canning safety.

While it may feel difficult to question the recipes passed down by loved ones, doing so is not a betrayal. It’s an act of reverence. Honoring the heritage means keeping the tradition alive and safe. By integrating history with evolving knowledge, we ensure that canning remains a powerful, empowering, and life-sustaining craft for generations to come. After all, since its inception, the art of canning has always evolved. Embedded in its history and tradition is the continual refinement of recipes and methods. Growth is, in fact, traditional.

Sadye H. Wier (center) with Donald Perry and Mary Spearing, pictured in front of Prairie Opportunity, Inc. Community Cannery in Macon, Mississippi. 1976 ,source

In the simple act of home canning, we are preserving a legacy—not just of food, but of care, skill, and resourcefulness. Even when we use newer, tested, and updated recipes, we remain part of the same tradition. And not all of Grandma’s recipes need to be completely discarded—they may only need a few tweaks. Adding an acid like citric or bottled lemon juice, adjusting the processing time, or simply swapping out an old peach canning recipe for a current and tested one can make all the difference. The result will be essentially the same—delicious, meaningful, and safe.

The magic isn’t only in the recipe; it’s in the hands that carry the knowledge forward, adapting with time while honoring the past. In this work, we become co-creators of home canning’s future—the book has not yet been fully written. Each of us has the opportunity to sign our name in the author’s space.

It’s not an honor to take lightly—when we imbue what we create with integrity at every step, the results can only be extraordinary. Whether we’re professionals or home cooks, this collective effort brings a unique light into the world. Pride in craft is being lost at an alarming rate, but all it takes to slow that loss is veneration and intent. I believe each of us holds that power—and the choice to use it is ours alone.

A pile of pumpkins in Grandma Clara’s yard in Royal City. My sister Katrinka sits atop, wearing red. This is the yard and house where I fell in love with gardening, canning, and community food processing. The memories here are so special, it’s hard to put them into words.

Where to Find Safe, Tested Recipes for Home Canning:

If you're ready to begin canning or update your methods, there are many trusted resources available that provide evidence-based, safe recipes and guidelines. Here are some of the most reliable sources:

National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP)

An excellent resource for everything related to home food preservation, from canning to freezing, drying, and fermenting. Their recipes are science-based and regularly updated.

Visit the NCHFP websiteBall Canning

Known for its iconic canning jars, Ball provides a wealth of recipes, guides, and resources for safe home canning. Their tested recipes are great for beginners and seasoned canners alike.

Explore Ball Canning RecipesUSDA Home Canning Resources

The USDA offers comprehensive, up-to-date guidance on safe home canning practices and recipes for low-acid and high-acid foods.

USDA Complete Canning GuideUniversity Extensions and Master Food Preservers

Many universities offer local programs and courses for home canning and food preservation. They provide free or affordable resources, recipes, and instructional materials. Look for your local university extension’s food safety and preservation resources.

For example, check out the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources website for reliable home food preservation information.

UC ANR Home Food PreservationOther Trusted Websites:

Healthy Canning: A trusted site with a variety of science-backed recipes.

Visit Healthy CanningThe National Agricultural Library: A useful resource for historical data and modern canning practices.

Explore the NAL site

By using these resources, you’ll be sure to can with confidence, knowing that the recipes and techniques are safe, scientifically supported, and up-to-date.

Additional Resources Used for This Article:

https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/ipd/canning/timeline-table

https://www.nal.usda.gov/exhibits/ipd/canning/exhibits/show/results/botulism